Commodity Money and Fiat Money: A Bushel of Wheat for a Penny

A Bushel of Wheat for a Penny Part 1

by Steve Elwart, IDB Folio Specialist

Republished with permission from Koinonia House

-

This is Part 1 of a three-part series on money: where it comes from, how governments use it to control our lives, and how modern money policy makes the prophecies in the Book of Revelation seem very close to fulfillment.

Everyone reading this article is being robbed. We all use paper money and every day, governments are lowering its value. That value is being stolen from us. To understand how this is happening, we need to get to the basics of money. What is it?

Commodity Money

We learn in Genesis that Abram (renamed later by God to Abraham) was a rich man. How do we know? We are told that “he had sheep, and oxen, and he asses, and menservants, and maidservants, and she asses, and camels.”1 In Biblical times, these things were all media of exchange. No king decided this; he didn’t call in his magi to decide what the medium of ex-change would be. Ordinary people, or “the market” made the decision. Let’s say a king did decree that rocks could be used as money. Would anyone use them? Probably not, because they would not know the value of those rocks. Unless you are building a lot of things (or stoning a lot of adulterers), rocks fail to meet a standard for money: they have no intrinsic value.

If a civilization was to advance though, it had to come up with a convenient way to save and exchange value to buy things. Leather was used in ancient Rome. (Contrary to popular belief, Roman soldiers were not paid in salt. The term salary [from the Latin salārium] was money given to Roman soldiers to buy salt.2) Animal pelts, whiskey, and tobacco leaves were used in the former British Colonies, wampum (strings of beads) was used by the American Indians, dried fish were used in the Canadian maritime colonies, maize or corn was used in Mexico, and salt, iron and farming tools were used in Africa. These things are called “commodity money.” As civilizations became more complex, most forms of commodity money be-came very cumbersome. (Who would want to give or get 300 sheep to buy a car?) Another medium of exchange had to be found.

Over the centuries, the answer came to be the precious metals, gold and silver. These two metals became the basis for money in most of the world. Gold and silver were used as money for very specific reasons and they were chosen by “the market.” People decided that these two metals had all the qualities that made for a good medium of exchange:

- They were easily portable. They had high value to weight ratios. (So if you want to buy a car, you only have to bring 16 ounces of gold rather than 300 sheep.)

- They are fungible. Every ounce is like every other ounce no matter where they were mined. People didn’t have to worry about the quality of the pure metal.

- They are highly divisible. They can be divided into very small parts or coins. The term “pieces of eight” came from the practice of taking a Spanish dollar, a real de a ocho and breaking it up into eight pieces or reales to make change. Diamonds fail the test of being divisible because if you break up a gem-quality diamond, it loses its value. (For that matter, sheep aren’t easily divisible either unless you are very hungry.)

- They are highly durable; the thirty pieces of silver paid to Judas are still in existence today.

- They are naturally scarce. They can’t be multiplied.

Fiat Money

There is another type of money besides commodity money, called fiat money. (Fiat from the Latin fiat, meaning “let it be done.”) This is an item, usually paper or low value metal coins, that is decreed to have value by a government.

A government puts fiat money into circulation first by connecting it to a gold or silver standard, but then cuts the link and says that gold and paper are no longer convertible, making the piece of paper “legal tender for all debts public and private.” It is obvious that debtors would be very happy if the pa-per money lost its value because they could pay their debts with inflated currency. In a letter to Edward Carrington in 1788, Thomas Jefferson wrote, “Paper is poverty … it is only the ghost of money, and not money itself.” Jefferson died bankrupt because of the early United States money (monetary) pol-icy based on paper.

It is not that fiat currency is a new invention. Fiat currency actually made its appearance over 1,000 years ago. China was the first country to issue true paper money around the 10th century A.D. Although the notes were valued at a certain ex-change rate for gold, silver, or silk, conversion was never allowed in practice. The bills were supposed to be redeemed after three years in circulation, but as more bills were printed with the older notes being refused redemption, inflation became evident. Government measures to prop up the currency were unsuccessful and it fell out of favor.3

In Europe, fiat money came into being around the 12th century. Villagers would store their gold and other valuables in their lord’s castle for safekeeping. But during this time of the Crusades and other European Wars, noblemen were always strapped for cash. When times were particularly bad, the noblemen would confiscate the villagers’ gold and silver and issue notes for it, to be redeemed later. Needless to say, the notes weren’t always honored or if they were redeemed, the holder of the note received less of their gold back than what they were promised. This is an early case of price inflation.

Today, fiat money will always bring on inflation for two reasons: 1) Politicians like to induce inflation because it gives the people the illusion of prosperity and 2) its declared value is much higher than the cost of producing it. Whether it is a $1 or $100 bill in fiat money, it costs only 4 cents to produce. In today’s electronic age, the production cost for new money is zero since money creation is just a keystroke and an entry in cyber-space. On the other hand, in history, if you had a $20 gold piece, the cost of that gold piece, less the cost to produce it, was about $20.

The Gold Standard

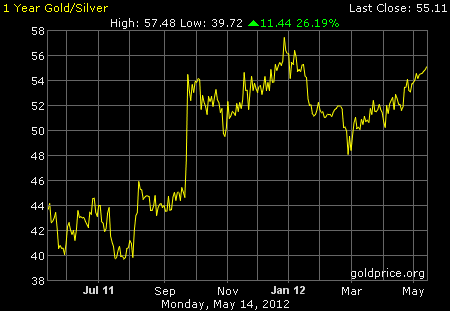

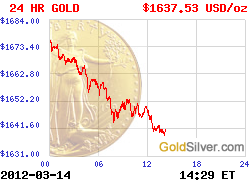

If the relative value of gold is tracked over the years, one can see how fiat money loses its value over time.

By the 1400s, most countries that had complex trading systems were using gold and silver for transactions. Prices held relatively steady through the early 20th century, except for lo-cal shortages and wars. In the United States the price of gold and the things it bought held its value with exceptions for war-time when the government printed paper money to cover its war debts. After the emergencies and the country went back on the gold standard, prices went back to about where they were. During the First World War, most countries involved in the war suspended the gold standard so they could print enough money to pay for their involvement in the war. After the war, these countries went back to a modified form of the gold standard, but abandoned it during the “Great Depression.”

In 1941, most countries adopted the Bretton Woods system, which set the exchange value for all currencies in terms of gold. Countries that signed the Bretton Woods agreement were obligated to convert their currencies held by foreign countries into gold valued at $35 per ounce. However, many countries just pegged their currency to the U.S. dollar, thus making it the de facto world currency.

In the 1960s the United States had done something unprecedented in its history. The country fought two wars at once. The United States fought a war halfway around the world in Vietnam and a second war at home, the “War on Poverty.” To do this, the United States started to borrow massively and brought on double digit inflation. To curb the inflation, the United States government started to deflate the dollar. 1963 marked the entrance of the new Federal Reserve notes and the disappearance of the $1 silver certificate. This marked the point that no longer did the U.S. Government have to pay in “lawful money.” Finally, in late 1973, the U.S. government decoupled the value of the dollar from gold altogether and the price shot up to $120 per ounce in the free market.4 Since the United States went off the Gold Standard, a dollar is worth only one-sixth of what it was in 1973. (At this writing, gold is priced at $1,220 per ounce.5)

Inflation Always Follows Fiat Money

The history of price inflation in the United States is repeated in every country that uses paper money. Keep in mind, rising prices are not always bad. If a good becomes scarce, its price will go up and may provide the motivation to introduce a new, better product for the market. The reason petroleum became so popular so quickly was because of the rising cost of whale oil. If governments propped up the price of whale oil to keep whalers and whale oil processors employed, it would have taken decades for the world to embrace petroleum as a substitute. And someday, petroleum will go the way of whale oil as long as market forces dictate the transition.

When a government inflates its currency, it increases prices by reducing the purchasing power of the money. The short-term effects though, can seem to be positive. Like a drug addict, inflated money gives the illusion of prosperity, making people feel good. But like the addict, withdrawal follows the high.

At first, the surge of more money makes people feel good be-cause they can pay off their debts with cheaper money and they seem to have more disposable income. As prices catch up, people then find it more expensive to live. In addition, their tax burden goes up, since many government taxes are progressive in nature, meaning the percentage tax increases as in-come or asset values (houses, cars, etc.) increase. Eventually the market will try to correct itself and a depression will follow.

At this point, people start to feel the pinch of their money buying less. They demand that their government do some-thing. Since studies have shown that voters only have a memory of one year when it comes to politics, politicians will make sure that the economy is good in an election year.6 They will artificially stimulate the economy to give voters the illusion that times are good again and reelect the incumbents. This lasts only so long and inflation, with its problems kick in again. This cycle of increasing the currency supply and price inflation ultimately ends with the collapse of the currency, sometimes preceded by hyperinflation. (Hyperinflation and its cultural effects will be covered in Part 3 of this series.) Surprisingly, the country has not learned its lesson and the devalued fiat currency is replaced with yet another fiat currency. Greece is a perfect example of this cycle.

The Greek drachma was minted in gold and silver in ancient Greece and made its reappearance as a fiat currency in 1841. Since then, the value of the drachma decreased. During the German-Italian occupation of the country from 1941-1944, hyperinflation ravaged the country, ending with the issuance of 100,000,000,000 (100 billion)-drachma notes in 1944. After Greece was liberated from Germany, old drachmae were ex-changed for new ones at the rate of 50,000,000,000 to 1. Only paper money was issued, again a fiat currency. Greece then went on a program of deficit spending for social programs and inflation started once again.

In 1953, in an effort to halt inflation, Greece joined the Bretton Woods system and the drachma was revalued at a rate of 1000 old drachma to one new drachma. In 1973 the Bretton Woods System was abolished; over the next 25 years the official exchange rate gradually declined, from 30 drachmas to one U.S. dollar to a ratio of 400:1. On January 1, 2002, the Greek drachma was officially replaced as the circulating currency by the Euro (again a fiat currency).7

Today, Greece is once again is in trouble. After years of continued deficit spending and the government’s easy monetary policy, Greece’s financial situation was badly exposed when the global economic downturn struck. Very quickly, the government’s “creative accounting” practices were exposed. The national debt, put at €300 billion ($413.6 billion), is bigger than the country’s entire economy, with some estimates placing it at 120 percent of gross domestic product in 2010. The country’s deficit—how much more it spends than it takes in—is 12.7 percent.

This time though, Greece just can’t inflate their way out of the problem. Now that they are on the Euro (in the “Euro-zone”), they have little control over their monetary policy. All their loans are in Euros and they must pay back the loans in Euros. One way to balance the national books is to implement harsh and unpopular spending cuts. Another way is to default on their debt. This would seriously damage the Euro as other countries look at default as a way out of their financial problems. (In fact, financial experts are predicting the demise of the Euro in as early as five years.8) A third way out is to separate itself from the Euro, go back on the drachma (fiat currency again) and then set an exchange rate of the drachma to the Euro at an artificially high number. The cycle of fiat money would then begin again.

As long as a country is on a fiat currency, inflation is sure to follow. Using a fiat currency could well reduce a civilization to work an entire day for a “bushel of wheat.”

In Part 2 of this series we will look at central banking and how the banks can change a society.

Notes:

- Genesis 12:16b (KJV).

- “The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th edition”. Answers.com. Retrieved 2010-06-05.

- Ramsden, Dave (2004). “A Very Short History of Chinese Paper Money.” James J. Puplava Financial Sense.

- History of the Gold Standard: http://useconomy.about.com/od/monetarypolicy/p/gold_history.htm

- Monex Precious Metals: http://www.monex.com/monex/controller?pageid=prices.

- “Voters Respond to Economic Woes” Economics and Public Policy: http://knowledge.wpcarey.asu.edu/article.cfm?articleid=1668.

- Greek Drachma, Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greek_drachma#First_modern_drachma.

- “Euro ‘will be dead in five years’”: http://www.telegraphic.com.uk/finance/financetopics/budget/7806065?Euro-will-be-dead-in-five-years.html

More Charts: 1-Month, 1-Year, 5-Year, 10-Year

More Charts: 1-Month, 1-Year, 5-Year, 10-Year More Charts: 1-Month, 1-Year, 5-Year, 10-Year

More Charts: 1-Month, 1-Year, 5-Year, 10-Year