How gold became politically correct

It all started very quietly with a little-known speech in May of 2008 by Benn Steil, a highly respected policy insider at the the Council on Foreign Relations. The CFR is generally considered the font of establisment thinking on foreign and international economic policy. Steil’s speech had to do with gold — an unusual subject for someone so prominent in the CFR. His proposal? That gold should be restored to a central role in the international monetary system.

Steil’s proposal had an immediate impact. Reports began to filter into the markets that certain central banks were beginning to accumulate gold bullion as part of their reserves. Some went about their acquisitions quietly. Others pursued their interest in the open. India, for example, made a highly publicized 200-tonne purchase from the International Monetary Fund. Simultaneously, traditional gold sellers, like many of the European central banks, shelved selling plans. Sales under the Central Bank Gold Agreement came to a standstill. It was about this time, too, that reports began to surface of a very strong developing interest in gold bullion among major hedge fund operators.

|

|

|

|

|

Benn Steil

Council on Foreign Relations

|

Robert Zoellick

World Bank President

|

Thomas Hoenig

Kansas City Fed President

|

Alan Greenspan

Former Fed Chairman

|

By 2010, policy notables like Robert Zoellick, president of the World Bank, Thomas Hoenig, president of the Kansas City Federal Reserve, Randall Forsyth of Barron’s magazine and Indiana Congressman Michael Pence, an oft-mentioned contender for the 2012 presidential sweepstakes, had come public with their own support of a new role for gold in the world’s monetary system. Hoenig stated that the gold standard is a “very legitimate monetary system.” Pence suggested that “the time has come to have a debate over gold, and the proper role it should play in our nation’s monetary affairs. A pro-growth agenda begins with sound monetary policy.” Zoellick wrote in Financial Times that gold should be looked upon as a means to stabilizing the global monetary system. In January, 2011, former Fed chairman Alan Greenspan noted in a Fox Business interview that “There are numbers of us, myself included,who strongly believe that we did very well in the 1870 to 1914 period with an international gold standard.” Suddenly, and to some inexplicably, gold had gone from hopelessly out-of-style in policy circles to highly fahionable. Gold, in fact, suddenly had become politically correct.

nation’s monetary affairs. A pro-growth agenda begins with sound monetary policy.” Zoellick wrote in Financial Times that gold should be looked upon as a means to stabilizing the global monetary system. In January, 2011, former Fed chairman Alan Greenspan noted in a Fox Business interview that “There are numbers of us, myself included,who strongly believe that we did very well in the 1870 to 1914 period with an international gold standard.” Suddenly, and to some inexplicably, gold had gone from hopelessly out-of-style in policy circles to highly fahionable. Gold, in fact, suddenly had become politically correct.

The new role for gold narrows down to two options covered below. The first is to return to a fixed-price gold standard similar to the post World War II Bretton Woods arrangement. The second is for gold to take on a role similar to the one it now plays in the European Union. In either instance, the best-positioned investors, for reasons outlined below, will likely be the owners of the physical metal itself, although those who own the right gold-mining companies could also gain significantly over the longer run, as the need for sizable new production becomes increasingly apparent.

Option #1 - Bretton Woods II, the traditional gold standard

Recently Alan Greenspan surfaced as probably the most prominent advocate of the gold standard. “We have at this particular stage a fiat money,” he said, “which is essentially money printed by a government, and it’s usually a central bank which is authorized to do so. Some mechanism has got to be in place that restricts the amount of money which is produced, either a gold standard, a currency board, or something of that nature.” Without it, he warned, “all of history suggests that inflation will take hold with very deleterious effects on economic activity.”

Much of the discussion on a return to the gold standard has centered around resurrecting Bretton Woods, which was the operating monetary system from just after World War II to the early 1970s. Under Bretton Woods, the price of gold was fixed at $35 per ounce and all the currencies, in turn, traded at fixed exchange rates relative to the dollar. This arrangement broke down in 1971 when president Richard Nixon closed the gold window. Continued redemptions at the $35 benchmark eventually would have depleted the U.S. gold reserve. Nixon declared that “we are all Keynsians now” and the world went on the fiat money system that is still in operation today.

Much of the discussion on a return to the gold standard has centered around resurrecting Bretton Woods, which was the operating monetary system from just after World War II to the early 1970s. Under Bretton Woods, the price of gold was fixed at $35 per ounce and all the currencies, in turn, traded at fixed exchange rates relative to the dollar. This arrangement broke down in 1971 when president Richard Nixon closed the gold window. Continued redemptions at the $35 benchmark eventually would have depleted the U.S. gold reserve. Nixon declared that “we are all Keynsians now” and the world went on the fiat money system that is still in operation today.

To make a gold standard work today, the metal would have to be valued at a very high dollar price to address the imbalances already existing in the world’s reserve system, and to make it possible for the new system to function smoothly and equitably. If, for example, one were to value the U.S. gold reserve high enough to cover the U.S. national debt of over $14 trillion, gold would have to be benchmarked at over $50,000 per ounce. To cover the external U.S. debt of $4.3 trillion, it would need to be valued at $16,500 per ounce.

|

Though $50,000 an ounce, or even $16,500 an ounce, may be significantly more than would be required to restore order in the monetary system, too low a price would recreate the same problems which caused the abandonment of Bretton Woods in the first place. To make a gold standard work, policy-makers will be called upon to choose a price that would bring balance between the roughly 8000 tonne U.S. gold reserve and the massive dollar reserves that have built-up all over the globe. To be sure, it is unlikely such balance would occur in the current price range.

Beyond the pricing problem, a return to a fixed gold standard presents additional challenges. The essential reason for a gold standard is to restrict governments’ ability to run deficits and print money. When politicians consider the problems faced by countries like Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain during the recent European sovereign debt crisis, they will not fail to note that in each instance those nation-states had relinquished their monetary sovereignty to the larger European Union. The options to run deficits, print money and debase the currency as a means to an end were off the table. Those who read their history texts carefully will be quick to point out that the gold standard offers major benefits, like a low inflation rate, balanced trade accounts and a strong currency. However, for all its benefits, it also conjures up images of deflationary depressions and financial panics, which would imply the kind of economic chaos that plagued the world economy intermittently under the gold standard before World War II.

In an imperfect world, no monetary system is without flaws. There are tradeoffs, imperfections, and a downside no matter what kind of monetary architecture is employed. Recognition that there are limitations to any monetary system might be the strongest argument for gold coins and bullion as an evergreen portfolio item. In the end, the gold standard is prone to deflationary breakdowns and the fiat money standard is prone to inflationary or stagflationary breakdowns. In the era of the nanny state, it is not too difficult to guess which of the two poisons is more palatable politically, and that is why a true Bretton Woods II accord is unlikely to get beyond the talking stage, despite the endorsement of luminaries like Alan Greenspan.

Option #2 - The European Union’s mark-to-market model

The more likely, and probably preferrable course, of action is for governments to use gold in a fashion similar to that employed by the European Union in 1999 when it introduced the euro. Robert Mundell, the Nobel Prize winning economist and “the intellectual father of the euro,” advised the European Central Bank (ECB) to use gold as part of its reserves. By doing so, he reasoned, it would offset the dangers of holding national currencies capable of being debased. In other words, he recommended that the ECB own gold for the same reasons any individual would.

The more likely, and probably preferrable course, of action is for governments to use gold in a fashion similar to that employed by the European Union in 1999 when it introduced the euro. Robert Mundell, the Nobel Prize winning economist and “the intellectual father of the euro,” advised the European Central Bank (ECB) to use gold as part of its reserves. By doing so, he reasoned, it would offset the dangers of holding national currencies capable of being debased. In other words, he recommended that the ECB own gold for the same reasons any individual would.

The European Union took his advice. Its gold reserves proved to be a bulwark and an example amidst the currency wreckage during gold’s run-up from €246 per ounce in 2001 to €1055 per ounce at the end of 2010. From 30.5% of Eurosystem’s net international reserves in 1999, gold went to 67.1% of net total reserves helping bring relative stability to the euro currency despite the union’s sovereign debt problem.

In the run-up to Chinese President Hu Jintao’s recent visit to the United States, he took time off from spreading mega-doses of financial largesse among troubled European nation-states to bluntly criticize the dollar-based international currency system. Calling it a “product of the past,” he suggested a new system that would be more “fair, just, inclusive and well-managed.” Obviously, Hu sees in all this a stronger roll for China’s currency, the yuan. More importantly to Americans, like a good many of his counterparts across the globe, he also foresees a diminished role for the U.S. dollar.

China enjoys the unique distinction of being both the world’s largest producer and consumer of gold. Its attachment to the yellow metal, like India’s, is deep-seated and goes back to ancient times. The People’s Bank of China is on the record for advocating a target reserve holding of 4000 tonnes — roughly half that of the United States. If we are indeed at the dawn of a new world economic order as many suggest, then China’s place in it will be an important one, and its views on gold will become an important element to any discussions of a new monetary system.

China enjoys the unique distinction of being both the world’s largest producer and consumer of gold. Its attachment to the yellow metal, like India’s, is deep-seated and goes back to ancient times. The People’s Bank of China is on the record for advocating a target reserve holding of 4000 tonnes — roughly half that of the United States. If we are indeed at the dawn of a new world economic order as many suggest, then China’s place in it will be an important one, and its views on gold will become an important element to any discussions of a new monetary system.

When Robert Zoellick’s proposal on monetary gold was published in November, 2010, it was seen by many as a call for a return to the gold standard. A close review of his remarks, however, tells a different story. Zoellick himself has said that those who read his proposal as a return to the gold standard were off the mark. Instead, he said, gold should play a role “as a reference point for market expectations of inflation and future currency value.” Under such a system, if gold were not allowed to float in value against the various currencies, it could not serve as a viable “reference point.” In other words, Zoellick proposed a role for gold in international currency reserves similar to the one it plays at the European Central Bank. Benn Steil too echoed the thinking of Robert Mundell in his speech delivered in 2008:

“. . .if you go down the line of currencies around the world, you don’t find many attractive opportunities. And that’s why I say if the world were to give up on dollars and give up on euros, they’d probably go back to the old standby, which is gold. And I don’t mean by gold, government run gold standard, like we had in the late 19th century. That’s politically impossible. Governments will never be willing to subordinate their policies to the constraints of a hard commodity ever again… So how could gold make a revival as a sort of international money? Well, we don’t actually need a government run gold standard anymore…since people have always had confidence in gold as a long-term store of value, there’s no reason why it couldn’t play that role.”

Where do we go from here?

As you can see, the calls for gold’s return are not really centered around the gold standard at all, but a role for gold as an alternative, no-strings-attached currency reserve. What would such a change in gold’s official sector function mean for the private citizen who also happens to be a physical gold owner?

First and foremost, instead of gold being an enemy of the state, it would become a friend. Instead of being a pariah among some key central banks, it would become an honored guest. Instead of being sold and leased by central banks, it would come under accumulation, particularly by those nation-states which are light the precious metal (e.g. India, China and Japan).

First and foremost, instead of gold being an enemy of the state, it would become a friend. Instead of being a pariah among some key central banks, it would become an honored guest. Instead of being sold and leased by central banks, it would come under accumulation, particularly by those nation-states which are light the precious metal (e.g. India, China and Japan).

In short, all of those things that gold labored against mightily over the past several decades would be suddenly removed. In the years ahead, that change in thinking could turn out to be among the most important baseline results of the financial crisis for economic policy-makers and for ordinary investors alike.

Thomas Kaplan (Tigris Financial Group) put it this way in aFinancial Times opinion piece titled “Brace for a Perfect Storm in Gold”:

“I believe the renewed appreciation of risk management is in its infancy and that gold, like stocks and bonds, will recover its relatively small, but significant historical position in the world’s investment funds. Considering the tiny size of the gold market, the implications of a potential return of gold into the world’s largest portfolios are enormous. For, unlike stocks and bonds, whose supply can increase to meet demand, there is not enough gold to go around at today’s prices.”

It could very well have been in anticipation of this landmark change in international monetary dynamics that some of the most revered hedge fund operators in the world (George Soros, Paul Tudor Jones, John Paulson, David Einhorn, Eric Mindich - to name a few) began to accumulate gold in bullion form. In some hedge funds, like Soros Fund Management, gold represents the largest position in their overall holdings. The funds with large physical holdings, in essence, are positioning themselves to become the gold banks of the future. Among other possible outcomes, if the world’s nation-states were to agree to gold playing a role similar to the one described by Steil and Zoellick, gold could come under the kind of demand pressure that would send it soaring to the next level — a circumstance that refreshes the old adage “he (or she) that owns the gold, makes the rules.” That sentiment applies not just to gold-heavy hedge funds, but to the well-positioned private owner as well.

- -

nation’s monetary affairs. A pro-growth agenda begins with sound monetary policy.” Zoellick wrote in Financial Times that gold should be looked upon as a means to stabilizing the global monetary system. In January, 2011, former Fed chairman Alan Greenspan noted in a Fox Business interview that “There are numbers of us, myself included,who strongly believe that we did very well in the 1870 to 1914 period with an international gold standard.” Suddenly, and to some inexplicably, gold had gone from hopelessly out-of-style in policy circles to highly fahionable. Gold, in fact, suddenly had become politically correct.

nation’s monetary affairs. A pro-growth agenda begins with sound monetary policy.” Zoellick wrote in Financial Times that gold should be looked upon as a means to stabilizing the global monetary system. In January, 2011, former Fed chairman Alan Greenspan noted in a Fox Business interview that “There are numbers of us, myself included,who strongly believe that we did very well in the 1870 to 1914 period with an international gold standard.” Suddenly, and to some inexplicably, gold had gone from hopelessly out-of-style in policy circles to highly fahionable. Gold, in fact, suddenly had become politically correct. Much of the discussion on a return to the gold standard has centered around resurrecting Bretton Woods, which was the operating monetary system from just after World War II to the early 1970s. Under Bretton Woods, the price of gold was fixed at $35 per ounce and all the currencies, in turn, traded at fixed exchange rates relative to the dollar. This arrangement broke down in 1971 when president Richard Nixon closed the gold window. Continued redemptions at the $35 benchmark eventually would have depleted the U.S. gold reserve. Nixon declared that “we are all Keynsians now” and the world went on the fiat money system that is still in operation today.

Much of the discussion on a return to the gold standard has centered around resurrecting Bretton Woods, which was the operating monetary system from just after World War II to the early 1970s. Under Bretton Woods, the price of gold was fixed at $35 per ounce and all the currencies, in turn, traded at fixed exchange rates relative to the dollar. This arrangement broke down in 1971 when president Richard Nixon closed the gold window. Continued redemptions at the $35 benchmark eventually would have depleted the U.S. gold reserve. Nixon declared that “we are all Keynsians now” and the world went on the fiat money system that is still in operation today.

The more likely, and probably preferrable course, of action is for governments to use gold in a fashion similar to that employed by the European Union in 1999 when it introduced the euro. Robert Mundell, the Nobel Prize winning economist and “the intellectual father of the euro,” advised the European Central Bank (ECB) to use gold as part of its reserves. By doing so, he reasoned, it would offset the dangers of holding national currencies capable of being debased. In other words, he recommended that the ECB own gold for the same reasons any individual would.

The more likely, and probably preferrable course, of action is for governments to use gold in a fashion similar to that employed by the European Union in 1999 when it introduced the euro. Robert Mundell, the Nobel Prize winning economist and “the intellectual father of the euro,” advised the European Central Bank (ECB) to use gold as part of its reserves. By doing so, he reasoned, it would offset the dangers of holding national currencies capable of being debased. In other words, he recommended that the ECB own gold for the same reasons any individual would. China enjoys the unique distinction of being both the world’s largest producer and consumer of gold. Its attachment to the yellow metal, like India’s, is deep-seated and goes back to ancient times. The People’s Bank of China is on the record for advocating a target reserve holding of 4000 tonnes — roughly half that of the United States. If we are indeed at the dawn of a new world economic order as many suggest, then China’s place in it will be an important one, and its views on gold will become an important element to any discussions of a new monetary system.

China enjoys the unique distinction of being both the world’s largest producer and consumer of gold. Its attachment to the yellow metal, like India’s, is deep-seated and goes back to ancient times. The People’s Bank of China is on the record for advocating a target reserve holding of 4000 tonnes — roughly half that of the United States. If we are indeed at the dawn of a new world economic order as many suggest, then China’s place in it will be an important one, and its views on gold will become an important element to any discussions of a new monetary system. First and foremost, instead of gold being an enemy of the state, it would become a friend. Instead of being a pariah among some key central banks, it would become an honored guest. Instead of being sold and leased by central banks, it would come under accumulation, particularly by those nation-states which are light the precious metal (e.g. India, China and Japan).

First and foremost, instead of gold being an enemy of the state, it would become a friend. Instead of being a pariah among some key central banks, it would become an honored guest. Instead of being sold and leased by central banks, it would come under accumulation, particularly by those nation-states which are light the precious metal (e.g. India, China and Japan).

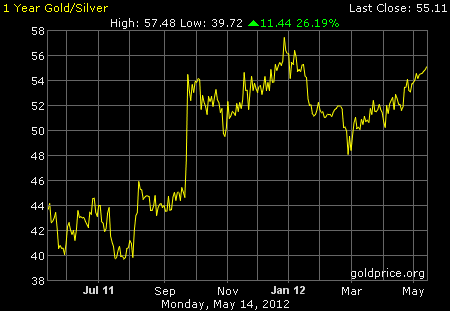

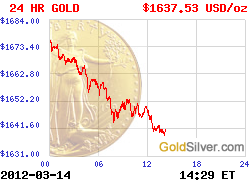

More Charts: 1-Month, 1-Year, 5-Year, 10-Year

More Charts: 1-Month, 1-Year, 5-Year, 10-Year More Charts: 1-Month, 1-Year, 5-Year, 10-Year

More Charts: 1-Month, 1-Year, 5-Year, 10-Year